Preventing injuries for 25 years

As a child, Matt Rhodes always wanted to learn how to swim. Most of his friends didn’t know how to swim either.

As a black child in Memphis, the likelihood of Matt being able to swim was slim.

Nearly 70 percent of black youth have no or low swimming ability. Along with Hispanic/Latino youth, they’re three times more likely to drown compared to their white counterparts, according to research from the University of Memphis.

Community efforts led by Le Bonheur Children’s Hospital have changed the course of the story for Matt and kids like him. Matt enrolled in a free water safety course offered by one of Le Bonheur’s injury prevention programs, Splash Mid-South.

“I joined Splash Mid-South because a lot of African-American kids like me don’t know how to swim, and I wanted to be different,” Rhodes said. “I wanted to learn how to swim in the deep end.”

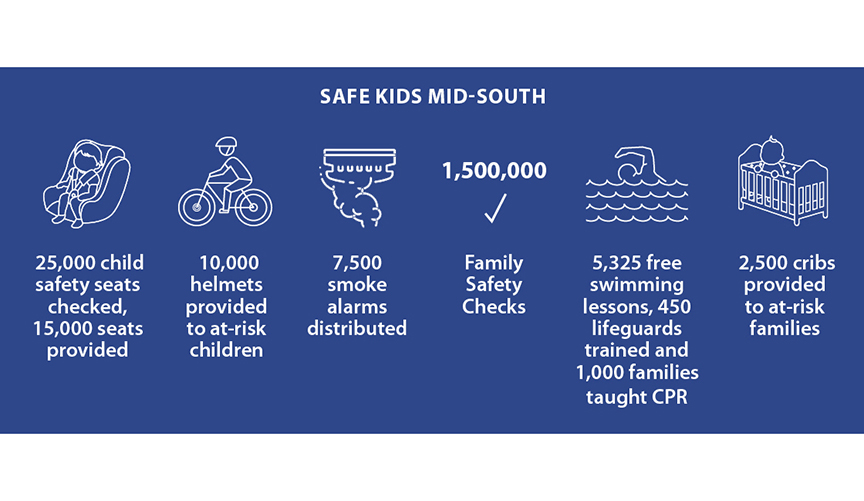

Rhodes, who now works as a lifeguard, is one of thousands of area children and families who have benefited from the hospital’s 25-year commitment to injury prevention in the Memphis area. Efforts range from redesigning pedestrian crossings around schools to helping parents properly install child safety seats.

Roots in the Intensive Care Unit

The community-wide safety campaign started with nurses and doctors who were concerned that many of the injuries they saw could have been prevented. Director of Injury Prevention Susan Helms, a former pediatric intensive care unit nurse, remembers two of her patients vividly.

A 12-year-old boy, who was the same age as her oldest son at the time, didn’t look before crossing the street. He was hit by a speeding car, and his head injury was fatal. The other was a young boy hit by a car while riding a bike. Without a helmet, the boy suffered injuries that required around-the-clock care at home.

“I remember after taking care of children who were in serious accidents, we’d often think, ‘if only there was child safety seat, or a smoke alarm or a helmet,’” Helms said. “When Le Bonheur had the opportunity to start a safety program, I knew the need was there.”

In 1992, the hospital joined the now global Safe Kids Worldwide, and Helms became the hospital’s director of Injury Prevention and Safe Kids Mid-South, a position she’s held since. Helms led efforts to review hospital trauma data, learn from parents, teachers and children through focus groups, unite with community groups and develop a comprehensive program to reduce injuries.

“Most people are surprised to learn that injuries are the No. 1 killer of kids in the U.S.,” Helms said. “In fact, nearly 8 million children and teens are treated in emergency departments each year. The cost of injuries is enormous and includes financial, emotional and societal impact — not only on the child but also the family, and the community as a whole.”

But there are things we can do to help prevent the accident from happening in the first place, says Helms.

The Safe Kids Mid-South coalition has grown to include 150 representatives from all emergency branches, businesses, schools, universities, churches, government leaders, health care workers and other advocates. The coalition develops efforts to address the greatest needs in the community. These partnerships have led to community-wide decreases in preventable injuries.

“One of the best ways to have a successful program that engages children is to have access to schools,” said Safe Kids Mid-South advisory board member Shane O’Connor, communications advisor with FedEx Global Citizenship. “Thanks to Susan’s professionalism and the ease with which she connects to school administrators, we have been able to engage children in schools across Memphis. Her training experience and expertise translates into effective engagement with students.”

Addressing the most prevalent injuries

In mid-90s, the coalition saw a rise in injuries from falls. While falls can occur many places, most occurred in homes. Helms worked with a developer, home builder and interior designer to build a home from the ground up with safety in mind. The house was open for tours so families could learn about potential hazards and ways to eliminate or minimize risks.

Safe Kids Mid-South was also instrumental in developing pedestrian safety curriculum with Safe Kids Worldwide and FedEx. In 1999, Walk this Way was piloted in three cities, including FedEx’s headquarters, Memphis. O’Connor worked on the original project with Helms.

“As a parent, I understand how important it is to know that your kids can make it to school safely, especially when they have to cross major boulevards and busy streets, as my kids had to do. With more than 150,000 vehicles on the world’s roads, it’s only natural that FedEx is concerned about road and pedestrian safety,” O’Connor said.

Walk this Way has reached more than 2 million children in 10 countries.

When Memphis’ Shelby County ranked No. 1 in the state for infant mortality (death before age 1), Safe Kids Mid-South worked with American department store Kohl’s to launch a program to address some of the causes. Since 2004, they have hosted baby safety showers, where more than 2,500 low-income mothers-to-be have received a crib, mattress and fitted sheets, a child safety seat and other household safety products.

Physicians leaders are part of the program’s advocacy efforts, speaking up for tougher laws for helmets, concussions and child safety seats. Le Bonheur’s Surgeon-in-Chief Trey Eubanks, MD, sees advocacy as a natural extension of the work of physicians.

“We in health care are the ‘content experts’ in health for our community,” Eubanks said. “Who could be better than us to explain to legislators and other stakeholders of the importance of injury prevention strategies to improve the health of our patients and their families?”

Collaborating for a safer future

Safe Kids Mid-South is based on collaboration – parents and children are actively involved in creating a safer community. For example, a child safety seat installation instruction has three steps for parents – learn, practice and explain. Before a parent leaves the check-up, they know how to safely and securely install a child safety seat because they’ve seen it, practiced it and explained it back to the instructor.

“We show and demonstrate how to fix it so children and families know what to do. We make sure what we do is data supported, research based and validated,” Helms said.

Le Bonheur has seen an overall drop in reported accidental injuries, with the largest decreases in bicycle, motor vehicle and pedestrian injuries. Helms says just as Safe Kids Mid-South has evolved to meet the current needs, she sees the organization adapting to address the challenges of the future. Programs in the works include distracted driving, furniture tip-overs and safe school designation programs.

Unintentional childhood injury is a problem that we as, a community, can fix. We will continue to learn, design strategies and educate parents and caregivers until safety is a part of every family’s fabric.”

Help us provide the best care for kids.

Le Bonheur Children's Hospital depends on the generosity of friends like you to help us serve 250,000 children each year, regardless of their family’s ability to pay. Every gift helps us improve the lives of children.

Donate Now