Life-Changing Potential

Just like other 4-year-olds, Sophia Cope enjoys being outside and watching Elmo, and her favorite colors are red, blue and green. But in one crucial way, she is one of a kind. Sophia is one of about 1,000 known cases of epilepsy caused by a mutation in the SCN2A gene. And now she is a participant in a clinical trial of the first medication to target this gene directly. If determined to be effective, this medication has the potential to change the lives of children with her diagnosis.

“This is the first time we have a therapy that we think can address the underlying cause to improve seizures and start seeing developmental improvement,” said James Wheless, MD, co-director of Le Bonheur’s Neuroscience Institute and principal investigator of the study. “If we can prove that it works, we can identify children who need intervention in the first week of life to stop developmental decline as early as possible.”

Le Bonheur Children’s is the only site in the world to enroll children in this phase of the EMBRAVE study for the medication PRAX-222 from Praxis Precision Medicines, Inc., with the goal of improving seizure control and development for children with this rare genetic epilepsy. Preliminary data has already shown success for patients with a 43% median reduction in seizures vs. baseline, an increased number of days without seizures and significant seizure reduction after just one dose.

Sophia Cope was one of the first children to participate in the EMBRAVE study for a gene therapy that addresses a genetic epilepsy caused by a mutation in the SCN2A gene.

SCN2A is the gene that directs the creation of sodium channel proteins in the brain, which control the flow of sodium ions to neurons. Mutations in the gene can cause too many or too few sodium ions to flow through the channels, causing epilepsy and developmental delay. In Sophia’s case, the gene caused her brain to overproduce sodium ions.

Children with an SCN2A mutation are typically born with no symptoms but start seizing within the first few days of life. Mutation of the gene can also lead to developmental delays that are further exacerbated by the presence of drug-resistant seizures.

Thanks to the Families SCN2A Foundation, the Copes learned about the EMBRAVE trial that might address the underlying genetic mutation causing Sophia’s medical conditions. And the only place in the world to participate in the trial was the hospital where their current neurologist, Amy McGregor, MD, was located — Le Bonheur Children’s.

The EMBRAVE study is investigating the efficacy and safety of the medication PRAX-222. This drug is a novel treatment called an anti-sense oligonucleotide (ASO), which targets genes at the mRNA level to affect protein expression. In this case, the ASO hopes to target the SCN2A gene to decrease its expression, which would then decrease the sodium ions causing the symptoms.

Delivered by intrathecal injection, trial participants will receive a dose of one milligram of PRAX-222 each month for four months. Patients are observed inpatient for at least 24 hours after the injection. Once this phase of the trial is complete, the

U.S. Food & Drug Administration (FDA) will reevaluate PRAX222 to determine if it can continue to the next phase of clinical trials.

“We have a deep track record of research in pediatric epilepsy, including intimate knowledge of taking a pre-commercial product and walking it through the regulatory phases required by the FDA,” said Wheless. “We also have a system for caring for children in a clinical trial with a very well-developed multidisciplinary program and experience delivering other ASO-based therapies for genetic epilepsies.”

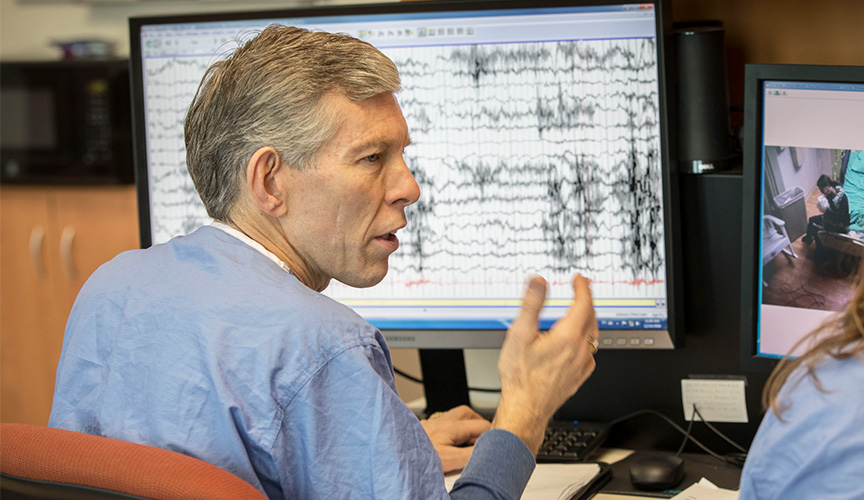

Le Bonheur Co-Director of the Neuroscience Institute and Chief of Pediatric Neurology James Wheless, MD, is principal investigator on the first study to address a genetic epilepsy caused by a mutation in the SCN2A gene.

If PRAX-222 is proved to impact the expression of the SCN2A gene, it has massive implications for children like Sophia. The drug could address the intractable seizures that occur multiple times a day. If diagnosed and treated early enough, the medication has the potential to drastically slow the developmental decline that is also associated with this gene’s mutation.

“We hope that it will provide enough of a fix for Sophia that she can still grow and reach what we call ‘inch-stones,’ sitting up, getting rid of her trach and becoming more active,” said Sophia’s mom, Michaela. “It’s great to think about how this can impact my child, but it’s also great to be a part of something that could get answers to help others.”

The Cope family says that they have already seen a reduction in the number and intensity of Sophia’s seizures and that she is awake more and very alert.

“Sophia has become more vocal as well — I believe that she has found her voice!” said Michaela. “She has made sounds before, but not often at all. Now we get to hear her on a daily basis and even several times a day.”

Help us provide the best care for kids.

Le Bonheur Children's Hospital depends on the generosity of friends like you to help us serve 250,000 children each year, regardless of their family’s ability to pay. Every gift helps us improve the lives of children.

Donate Now