A Voice for Every Child

Memphis Children’s Health Law Directive relies on collaboration among four community partners to address social determinants of health, legal barriers to health care

For Tim Flack, senior attorney of Memphis Children’s Health Law Directive (Memphis CHiLD), joining Le Bonheur Children’s Hospital’s medical-legal partnership felt like coming back home. His oldest daughter Madeline had been a patient at Le Bonheur since 10 months of age when she was diagnosed with four congenital heart defects, and the Flack family had already been involved as volunteers on the hospital’s Family Partners Council.

“Working at Memphis CHiLD allows me to really practice patient- and family-centered care more directly than I ever have and use what I was professionally trained to do,” said Flack. “The collaboration we have with community partners allows us to directly address the legal barriers to health care for the children in our community.”

Flack is one of four attorneys and a team of individuals including law students, medical students, medical providers and social workers, who form Memphis CHiLD — a unique medical-legal partnership among Le Bonheur Children’s Hospital, the University of Memphis Cecil C. Humphreys School of Law, Memphis Area Legal Services (MALS) and the University of Tennessee Health Science Center (UTHSC).

A CREATIVE PARTNERSHIP

Memphis CHiLD was unique among medical-legal partnerships (MLPs) from its inception. Unlike many MLPs, the four organizations came together before the program launched, sharing the same desire. Each wanted to partner and collaborate for the well-being of children. Formal talks began, and Memphis CHiLD launched in 2015.

Four attorneys are entirely dedicated to the program, including Flack — one of only two attorneys in the country directly employed by a hospital. The team accepts a wide variety of cases from patients and families — also unusual among MLPs, which typically limit cases to specific issues such as disability, housing or special education needs.

“Originally we focused on cases coming through our community asthma program,” said Flack. “But it soon became obvious that kids and families needed us to widen our net. While most partnerships focus on one or two case types, we will take almost any civil legal matter that is presented to us.”

Each partner plays a unique role in the collaboration to provide comprehensive legal care for kids and families. The program includes an attorney, social worker and social work intern from the hospital, law students and professors, a medical champion physician and dedicated teaching to medical students and residents.

“Partnership with all of these organizations is crucial in the effort to address social determinants of health and overcome the legal obstacles to child health and healing,” said Flack.

The majority of funding for Memphis CHiLD comes from grants and donors including Memphis’ Urban Child Institute. The unique partnership among the organizations is what drew funders to support the program and keep it sustainable.

THE COLLABORATIVE PROCESS

Collaboration on a patient’s case begins as soon as a patient or family is referred. Any Le Bonheur employee — physicians, nurses, social workers and others — can refer a family with a legal issue to Memphis CHiLD. The team determines if the family fits within the requirements, and they almost always do.

All team members of the partnership meet on a weekly basis to review cases. Going through referrals, they determine what each patient needs and who in the partnership can handle it best. Assistance runs the gamut from simple legal advice to a case that goes to trial. Memphis Area Legal Services (MALS), the primary provider of civil legal representation to low income families in western Tennessee, dedicates an attorney who works full time on cases from Memphis CHiLD.

“We ask ourselves: how can we stabilize the lives of a family as much as possible,” said MALS Chief Executive Officer Cindy Ettingoff. “Working in collaboration is really the key for us to obtain all of the underlying information to truly help. Medical professionals can’t really obtain everything needed for a child from a legal perspective, and we certainly can’t provide medical care.”

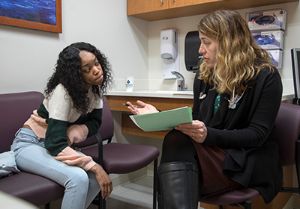

Le Bonheur employs Flack as senior attorney as well as Lydia Walker, LMSW, social worker for Memphis CHiLD. Walker works with cases that may or may not need to be handled legally. “Our case review process is all about how can we maximize our efforts and collaboratively get the best outcomes for the family,” said Walker. An important aspect of the process is connecting with a child’s physician and care team. This is unique among MLPs as families give lawyers permission to discuss health conditions with their child’s physicians.

Medical issues are interpreted by Le Bonheur Hospitalist and UTHSC Assistant Professor Emilee Dobish, MD, who leads the University of Tennessee Health Science Center’s part in the Memphis CHiLD collaboration. She serves as medical champion, promoting the program with Le Bonheur’s medical staff and serving as a resource for cases to interpret medical data. “It’s important for us to have a conversation about how the diagnosis impacts the child,” said Dobish. “Engagement from all medical disciplines is vital to break down legal barriers for families. Prior to this MLP, the legal issues would never have been on a physician’s radar.”

Armed with the appropriate medical information, lawyers are better able to represent patients to get the legal help they need. Patients and families receive legal advice and discuss their case at a Medical Legal Partnership Clinic.

Law students taking an interdisciplinary course through the University of Memphis Cecil C. Humphreys School of Law staff the clinic, which is led and directed by Assistant Professor of Law Katy Ramsey. Students simultaneously provide free legal services while receiving an education on the intersection of law and health. And for families whose needs extend beyond legal matters to social issues, social workers are able to step in to find housing and employment, work on individualized education plans or refer to other agencies that meet their needs.

BREAKING BARRIERS AS A TEAM

Memphis CHiLD’s role in helping families doesn’t stop with solving a single legal issue — ultimately, the partners work to address the social determinants of health that affect the patient and family. According to the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention, social determinants of health (SDOH) are the environmental conditions into which a person is born that can affect their health, including factors for greater risks and poor outcomes.

The team at Memphis CHiLD handles a wide variety of issues, but almost all of them are influenced by SDOH in some way. According to Walker, housing is a major issue in the Memphis area where the housing stock is outdated and families struggle with utility bills. Lawyers and social workers intervene to get improvements to housing conditions or find new housing for families. A large portion of the program’s legal cases center around supplemental security income (SSI) for children, particularly those who have been denied previously.

Memphis CHiLD’s experts know how to build the best case and present the right information to get approval. Beyond these issues, the team helps patients with specialized education needs, including 504 and IEP plans, conservatorships and Medicaid coverage.

“Families come in with one issue but have underlying barriers that prevent us from addressing that main issue,” said Walker. “There is always a social determinant of health involved and a social service need that can impact it.”

As a social worker, Walker is on the front lines addressing these social needs — her ultimate goal is to get families to a place of stability. While attorneys address legal aspects a family faces, Walker and her social work interns from local universities work with families on the practical aspects of their situation, including finding housing, securing funds and avoiding eviction. But not all MLPs have social workers attached to their program.

“Being a social worker in this program involves being a case manager, liaison, advocate and broker all at the same time,” said Walker. “The diversity in our role shows just how impactful the social work component of an MLP can be.” And while Walker is able to focus on individual families, the partners ultimately realize that it is vital to improve children’s health on a scale larger than individual families and affect more far-reaching change.

“For a long-term impact, we have to have community change, not just individual family success,” said Flack. “Using the knowledge we’ve gained about the barriers from social determinants of health that impact children’s health, we can translate this legal intervention to larger scale community change.”

To accomplish this, the partners at Memphis CHiLD focus on child health advocacy in the community in several ways. Through thought leadership, the partners work to inform the community and shape thinking around the intersection of policy and children’s health. The power of patient success stories are one way that the partners leverage advocacy and donor engagement. The program hopes that these tactics will affect policy change that breaks down barriers for families.

Ultimately legal intervention and social services have a direct impact on a child’s health. For example, finding stable housing for a child can reduce hospitalizations by reducing asthma triggers, mental stress and anxiety and minimizing stress levels. “Stable housing is like preventative medicine,” said Walker. “Hearing families release a sigh of relief because they no longer have to worry about this issue makes it all worth it.”

THE FUTURE OF MEMPHIS CHILD

As Memphis CHiLD has grown exponentially, goals for the future have as well. Plans are underway to formalize advocacy on behalf of children and families by collaborating with hospital and university leadership.

“We have to make sure that families will benefit long term — not just a drop in the bucket but access to full resources and lasting change,” said Ettingoff. “Children are our future. If we can help them, ultimately we are giving this community a healthy, productive adult in the future.”

A core objective of Memphis CHiLD is continuing to educate physicians on the function of the program to better assist with this vital role. UTHSC educates the next generation of physicians with an elective for residents taught by Dobish, covering the intricacies of the intersection of health and law.

Physician education will continue especially on plans for specialized education, IEP and 504 plans, to help prevent these cases from escalating to a legal issue.

Social work hopes to add new social workers, one for IEPs and one for housing, to intervene for families and avoid going to court. While the outcomes and data show the impact of the program, the stories of collaboration and family success are the best witness to how legal intervention can affect children’s health and the stability of a family.

“How do you quantify getting a landlord to clean up mold or establishing an IEP for a child?” said Flack. “Child advocacy among the partners of Memphis CHiLD is key to future sustainability of the program and greater impact on the community we serve.”

MEMPHIS CHILD BY THE NUMBERS

- Received more than 2,100 referrals

- Handled 1,500 cases

- Obtained $19,864.31 in social security income (SSI) monthly

- Obtained $256,662.92 in SSI back payments

THE WARD FAMILY

In September of 2017, Tammie Ward and her husband Roz were faced with a serious question: could they become parents for seven of their grandchildren?.

The children’s mother had experienced a mental crisis and was diagnosed with bipolar disorder, and in the wake of this event, the children were also diagnosed with an array of mental illnesses and developmental disabilities, including bipolar disorder, depression and autism. Who would be able to help the Wards through the adoption process and caring for the many needs these grandchildren had?

But thanks to a Le Bonheur nurse, the Wards were connected to Memphis CHiLD, Le Bonheur’s medical-legal partnership, and received the support, resources and legal expertise they desperately needed to care for their grandchildren. The nurse had been making home visits to care for Jeremie, the youngest grandchild who had cerebral palsy, scoliosis, was blind and required a feeding tube. She knew the Wards would benefit from additional legal support.

“Dealing with mental illness really took a toll on us at that time. We didn’t know anything about it, but we knew we needed to keep the kids in our home for the best opportunity for them to thrive,” said Tammie Ward. “Tim Flack (senior attorney at Memphis CHiLD) and his team came alongside us to walk through the legal system to get our kids what they needed.”

The Ward family received an array of resources and support from the Memphis CHiLD team. The Memphis CHiLD attorneys helped the children obtain social security and individual education plans (IEP) and walked the Wards through the process of adopting all seven of their grandchildren. Le Bonheur Social Worker Lydia Walker helped the family obtain everything from rent assistance to beds to Christmas dinner and gifts for the whole family. “We have gained more strength and knowledge since that first year we had the kids when we didn’t know what to do,” said Tammie Ward. “Just having someone like Lydia to talk to gave me strength.”

Their youngest grandchild Jeremie, died in his sleep in September 2019. But this tragedy only strengthened the Wards’ resolve to help others facing similar situations. Their experience with family members with mental illness even led them to create a non-profit, Seed House, Inc. Through this organization, the Wards aim to provide education and support to families of children with disabilities by connecting families with much needed resources in the community.

“Our journey with caring for children with disabilities prompted us to create something that would be a help to other families,” said Tammie Ward. “Where one person may see no hope, we believe there is hope for every child.”

Help us provide the best care for kids.

Le Bonheur Children's Hospital depends on the generosity of friends like you to help us serve 250,000 children each year, regardless of their family’s ability to pay. Every gift helps us improve the lives of children.

Donate Now