Fallout

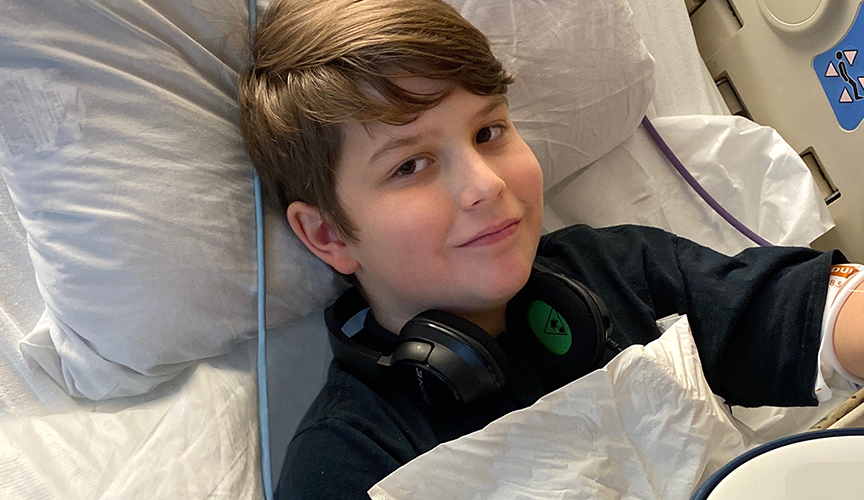

For Rhonda Crenshaw, COVID-19 has been the least of her worries for her 12-year-old grandson, Christian, in the past year.

Christian has faced multiple hospitalizations and surgeries that resulted from a terrifying dirt bike wreck, one of a growing number of pediatric trauma injuries that Le Bonheur has seen in the past year.

“My heart came out of my body when I heard Christian’s scream,” said Crenshaw. “I grabbed a dog leash to use as a tourniquet and waited for paramedics to arrive and transport him to Le Bonheur.”

Christian Fussell is one of many who have faced the unseen effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on children’s health. Though the virus has not infected children as extensively as adults, Le Bonheur pediatricians say that children’s health has still been negatively affected, in myriad ways.

These negative health outcomes result from social isolation, quarantine and extended time at home. Le Bonheur pediatricians have seen a decline in well child visits and vaccinations, educational difficulties for children with developmental disabilities participating in virtual school and the potential for increased psychopathology. They have also reported delayed access to critical rehab services needed for development and an uptick in trauma cases, particularly all-terrain vehicle (ATV) accidents such as Christian’s.

Five Le Bonheur providers discuss the unseen effects of the pandemic that they see regularly, what the long-term effects may be and what can be done to mitigate further health consequences to children.

General Pediatrics: Well Child Visits and Vaccinations

Missed well-child visits, vaccinations during COVID-19 pandemic require long-term strategies for catch up

Jason Yaun, MD, FAAP

Clinical Director of ULPS General Pediatrics

Division Chief of Outpatient Pediatrics

Medical Director, Family Resilience Initiative

In the early days of the pandemic, general pediatrician offices — including Le Bonheur’s — drastically reduced the number of well-child appointments until more was known about COVID-19. But once proper precautions were established and doctors’ offices reopened to a more normal capacity, Le Bonheur Pediatrician Jason Yaun, MD, FAAP, continued to see that parents were hesitant to bring in their children, for fear of the virus.

“While the number of visits in our office are beginning to reach similar levels as last year’s, we haven’t really seen any catch up from those who missed well-child visits and vaccinations during the beginning of this crisis,” said Yaun. “This is something that will have a long-lasting effect on the health and development of children.”

Yaun and his team continuously look for ways to mitigate this effect. For low-income families, delays exacerbate existing inequities, he said. He has also seen a tremendous gap in immunizations between families who are publicly and privately insured.

“Our initial strategy was to get kids going into kindergarten or seventh grade their required vaccines needed for school entry,” said Yaun. “We’ve had success by setting up clinics in the community, meeting our patients where they are. Long-term strategies are a must if we’re going to catch children up.”

But the effects on health go beyond the physical. Middle- and high school-aged children are facing numerous mental health challenges — whether families are dealing with the death of a loved one, community violence or feelings of isolation. The pandemic can be a type of adverse childhood experience (ACE) for many, which can result in a profound lifelong mental and physical health impact for kids, said Yaun.

Yaun connects patients with therapy and counseling through community resources, although he continues to see stigma and hurdles for families to get access to the needed mental health care. In the meantime, he continues to reassure parents that the doctor’s office is safer to visit than the grocery store. And supportive caregivers who demonstrate positive, nurturing interactions can support children and help them build resiliency to mitigate the negative consequences of ACEs.

“With many children on an irregular school schedule, routines, such as sleep schedules, balanced diets and physical activity, are an important, essential component of health,” says Yaun. “Continue to talk to children and discuss their social and emotional needs in an open and honest way to support and develop these skills.”

Developmental Health: Virtual School and Special Needs

Le Bonheur helps schools support children, avoid risks of falling behind in virtual school

Toni Whitaker, MD

Division Chief of Developmental Pediatrics, Le Bonheur and the University of Tennessee Health Science Center

Director, Leadership Education in Neurodevelopmental and Related Disabilities (LEND) Program, University of Tennessee Center for Developmental Disabilities

Le Bonheur Developmental Pediatrician Toni Whitaker, MD, is all too aware of the challenges school administrations, teachers and parents face with virtual school and students with special needs.

“We’re facing a difficult situation. Schools need to be physically safe and prevent the spread of COVID-19. But simultaneously they are trying to meet the unique needs of kids, especially those with developmental disabilities,” said Whitaker.

With many schools remaining virtual for so long, a truth remains: Younger children and children with developmental disabilities don’t benefit as well from virtual or online instruction. Both tend to learn at a slower rate and require hands-on guidance and immediate feedback to learn most effectively, said Whitaker.

Whitaker continues to see discouraged parents resigned to the fact that their children can’t learn as well with the circumstances of virtual school.

“We know from time periods where kids don’t have instruction, such as the summer, they lose progress but can often regain it with intensive instruction,” said Whitaker. “But we don’t have large groups we’ve followed who have been out of school for this extended period of time, particularly for children with developmental delays or special needs, to really know outcomes.”

To support schools and teachers, Le Bonheur formed a Back-to-School Task Force with the University of Tennessee Health Science Center (UTHSC), which provides guidance and information for schools as they safely return to in-person instruction with a special needs subgroup led by Whitaker.

“School staff who work with these kids daily are the experts in knowing what students with special needs require to learn effectively,” said Whitaker. “Our task force wanted to come alongside and provide information and support.”

Whitaker has also assisted families of children with developmental disabilities during the pandemic as the ambassador to Tennessee for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) “Learn the Signs. Act Early.” program. Using the new CDC grant funding, she will partner with state service agencies to train providers and distribute more than 30,000 free developmental monitoring and developmental promotion resources to families with young children.

Ultimately, Whitaker encourages families and schools to keep an open line of communication so that each can do what’s best for the child during a difficult time.

“Families need to interact one-on-one with their child as much as they are able, but also keep in touch with teachers and talk to their child about their experiences,” said Whitaker. “Therapy services and availability are evolving so continue to check in for your child’s needs.”

Trauma Services: Rising Trauma Occurrences Among Children

Pandemic brings increased trauma cases, gunshot wounds, with potential for generational impact

Regan Williams, MD

Medical Director, Trauma Services

The world slowed down as a result of the pandemic — but Le Bonheur Medical Director of Trauma Services Regan Williams, MD, has experienced the opposite in her patient population: Trauma injuries have risen since the pandemic began.

“When children spend more time at home, trauma cases rise,” said Williams. “Typically, cases drop when school starts. But with more children spending large amounts of time at home, sometimes unsupervised, numbers have remained elevated.”

She has seen a rise in trauma injuries in four major categories: non-accidental trauma, all-terrain vehicle (ATV) accidents, gunshot wounds and motor vehicle collisions.

But one area has Williams particularly concerned.

“Gunshot wounds have seen a concerning increase. Numbers remain high because kids are still at home,” said Williams. “This gun violence is turning into a pandemic within a pandemic.”

According to Williams’ initial data, trauma injuries will continue to rise or stay elevated until children are no longer spending extended periods of time at home. Gun violence in particular has devastating long-term effects on children, says Williams. Children who are victims of violent crime are more likely to end up in jail, be a victim again or be a perpetrator of violent crime.

“Le Bonheur only sees children 14 and younger with gunshot wounds. I worry that these children and young teens who are wrapped up in violence during this pandemic will continue to perpetrate it for years to come,” she said.

To mitigate these effects, Le Bonheur worked with the Shelby County Crime Commission, who organizes Walk Against Violence events to speak out against the gunshot violence in the city. Williams also represents Le Bonheur and the University of Tennessee Health Science Center as a part of the Memphis Group Violence Intervention Program. This effort plans to reduce violence in the city through five specific program areas: suppression, intervention, prevention, community mobilization and organizational change.

Williams believes much of the violence and trauma is a result of mental health issues and challenges. Le Bonheur recently partnered with the BRAIN CENTER at the University of Memphis so that all children treated at Le Bonheur’s Pediatric Trauma Center can be eligible for free mental health counseling services. Graduate-level students in the Clinical Mental Health Counseling program will provide the counseling.

“The pandemic has helped increase the conversation around mental health and show that the need for mental health support is clear,” Williams said. “People are lonely, mad and sad, including children.”

Psychiatry: Immediate and Long-Term Mental Health Effects of Pandemic and Isolation

Pandemic stressors historically lead to psychopathology in vulnerable youth

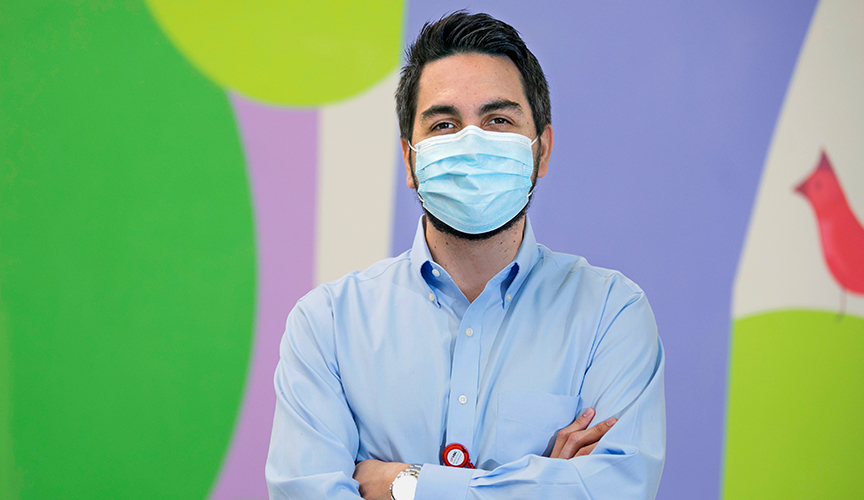

Andres Ramos, MD

Le Bonheur Psychiatrist

Whether it’s natural disasters, terrorist attacks or a deadly pandemic, psychopathology in children always follows, according to a wide variety studies conducted in the wake of these disasters.*

“With COVID-19, this is like a second pandemic — a wave of mental illness as a result of the initial pandemic,” said Le Bonheur Psychiatrist Andres Ramos, MD.

But kids are resilient, says Ramos. And while he doesn’t anticipate a long-lasting issue for masses of children, he admits that certain populations are far more at risk.

“Long-term effects exist for vulnerable kids during this pandemic as it does for any child who undergoes an adverse childhood experience (ACE) or develops post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD),” said Ramos. “Our hope is to figure out which COVID-related stressors are more likely to lead to psychopathology so we can intervene sooner with the children most in need.”

To do this, Ramos and his team are planning to conduct a study on psychopathology among Memphis’ Shelby County School System youth during the COVID-19 pandemic. The study will screen for PTSD and serious emotional disturbances (SED). SEDs are a wide range of psychopathological conditions, which would be classified as warranting clinical attention.

The individual stressors caused by the pandemic, from social isolation to sleep problems, are historically noted as leading to mental illness in children. But in the wake of COVID-19, these individual stressors are combined in previously unseen ways, according to Ramos. Social isolation increases risk of depression or anxiety for years after. Disrupted schooling leads young children to deviate from normal developmental milestones. Quarantine and isolation can also lead to sleep problems, inactivity and increased screen time, which have been shown to make children more vulnerable to psychological distress.

“The greatest areas of concern are for youth who are already vulnerable,” says Ramos. “With the COVID-19 pandemic, stressors are amplified in addition to what they already tackle every day.”

By determining which of these COVID-related stressors are most impactful to psychopathology, Ramos and his team can lead targeted mental health interventions in children. His team will provide community mental health resources for families engaged with the survey.

Finally, Ramos and psychiatrists have to consider the potential neurobiological effects of the virus itself.

“Coronaviruses are associated with the onset of mood and psychotic disorders,” said Ramos. “Inflammatory markers following COVID-19 illness predict depression and anxiety, and the concern is that the inflammation that clears the virus may also put those infected at risk for psychopathology.”

Overall, Ramos has hope of what the medical community and society at large can learn from this pandemic about the importance of mental health.

“This season is a humbling experience, but it doesn’t have to be a long-lasting psychological injury to children,” he says. “It’s an opportunity for learning and an evolution in how we think about people and the way circumstances affect mental health.”

*Main, A., Zhou, Q., Ma, Y., Luecken, L. J., & Liu, X. (2011). Relations of SARS-related stressors and coping to Chinese college students’ psychological adjustment during the 2003 Beijing SARS epidemic. Journal of counseling psychology, 58(3), 410.

Warheit, G. J., Zimmerman, R. S., Khoury, E. L., Vega, W. A., & Gil, A. G. (1996). Disaster Related Stresses, Depressive Signs and Symptoms, and Suicidal Ideation Among a Multi‐Racial/Ethnic Sample of Adolescents: A Longitudinal Analysis. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 37(4), 435-444.

McLaughlin, K. A., Fairbank, J. A., Gruber, M. J., Jones, R. T., Lakoma, M. D., Pfefferbaum, B., ... & Kessler, R. C. (2009). Serious emotional disturbance among youths exposed to Hurricane Katrina 2 years postdisaster. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 48(11), 1069-1078.

Schuster MA, Stein BD, Jaycox LH, et al. A national survey of stress reactions after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1507-1512.

Hoven CW, Duarte CS, Lucas CP, et al. Psychopathology among New York City public school children 6 months after September 11. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:545-552.

Rehabilitation Services: Barriers in Access to Care

Backlog of rehab referrals to Le Bonheur reflects lack of access to in-person care

Danielle Keeton, MA, CCC-SLP

Director, Le Bonheur Outpatient Rehabilitation & Developmental Services

Le Bonheur’s Outpatient Rehabilitation Services is facing a backlog of hundreds of children who could face long-term consequences to their development without rehab intervention, according to Danielle Keeton, MA, CCC-SLP, director of the department.

Keeton and her team of occupational, physical and speech therapists see multiple factors related to the pandemic that could lead to negative developmental outcomes for children — especially families with TennCare, Tennessee’s Medicaid program for children, who depend on Le Bonheur’s services.

The largest hurdle is the sheer number of children in need of rehab. A marked increase in trauma cases as a result of the pandemic increased the number of children who need immediate rehabilitation services. And when Memphis’ Shelby County Schools were following a 100% virtual model, children lost access to in-person therapy through school. Many of these children are covered by TennCare. According to Keeton, physicians refer to Le Bonheur’s rehab services in droves because it is difficult for families to find rehab centers where TennCare is accepted.

School therapists continue to provide services through telehealth. While highly effective for many kids, it requires large amounts of caregiver participation.

“We provide telehealth therapy services in our own school-based and early intervention programs, and it works very well. Only sometimes do acute needs require in-person evaluation, hands-on attention and specialized equipment to see progress,” said Keeton. “This is especially true for children with caregivers who, for very legitimate reasons, are unable to participate in telehealth sessions. We see parents juggling so many priorities right now.”

On top of this backlog: concern for missed developmental red flags that could lead to substantial future impacts.

“Without access to care, some children will see a loss in function,” said Keeton. “We won’t know all of the impact of missed developmental milestones for several years.”

Child care centers, schools and pediatrician offices serve as safety nets to catch children early who need therapy intervention for development. Closed child care centers, virtual school and missed doctor’s appointments mean that these preventative measures are missed.

But Keeton sees the pandemic as a wake-up call to the barriers that families and children have to access care, with so many depending on Le Bonheur’s limited resources without access to in-person therapy options through the school system.

“These inequities and social barriers to care have always been present, but the pandemic has raised more community awareness of the unmet support for families who have children with special needs,” said Keeton. “The success of a child is always about the success of the family.”

Help us provide the best care for kids.

Le Bonheur Children's Hospital depends on the generosity of friends like you to help us serve 250,000 children each year, regardless of their family’s ability to pay. Every gift helps us improve the lives of children.

Donate Now