Standing Up to Sepsis

Le Bonheur researchers pioneer pediatric tool

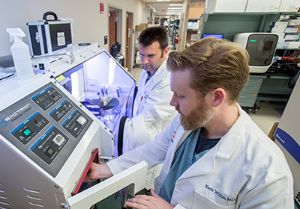

Nine years ago, Kimberley Giles, Le Bonheur’s Director of Decision Support, and Samir Shah, MD, Chief of Critical Care, realized they shared a vision: flagging sepsis as soon as possible.

“Every minute counts,” says Shah. “If you don’t intervene early, there’s a much higher risk of a negative outcome, whether it’s complications or mortality. Every hour that passes by without starting goal-directed therapy increases the odds of mortality. If you miss the golden hour, you’ve missed a critical window.”

Giles and Shah brought their departments together to build a tool to screen patients for severe sepsis in real time. Le Bonheur’s clinicians, decision support, information services and critical care staff have worked for nearly a decade refining an algorithm which integrates with a patient’s electronic medical record (EMR): the “first tool of its kind to be used in a pediatric center,” Shah says.

Sepsis, a suspicion of infection plus systemic inflammatory response syndrome, escalates to severe sepsis if left untreated. Severe sepsis, signaled by acute organ dysfunction and clinical signs such as low blood pressure, kidney failure and increased need for oxygen, leads to multiple organ dysfunction syndrome and death.

As care providers enter documentation and lab results into a patient’s EMR, the algorithm immediately scans for red flags.

The algorithm checks for combinations of criteria that may indicate severe sepsis, from patient age to lab results and vital signs. The moment a combination suggesting severe sepsis occurs, the algorithm fires an alert directly to an intensive care unit (ICU) nurse’s phone. The nurse and a physician then visit the patient, confirm severe sepsis and decide on treatment.

“Our job is to bring a team that can manage a child with severe sepsis in order to intervene quickly in a busy tertiary care children’s hospital,” said Shah.

The Cost of Sepsis

Swift intervention reduces cost, morbidity and mortality. The national pediatric treatment cost for severe sepsis rose from $4.8 billion in 20051 to $7.31 billion in 20162. In addition, sepsis, if allowed to progress, can cause residual damage from organ shutdown.

“If we don’t intervene early, these patients become severely septic, they stay in institutions longer, and even at the end of that, they

have a lot of morbidity,” says Shah. “There’s lung, kidney and liver injury.”

Giles and Shah’s initial goal was to curtail sepsis-related mortality.

Sepsis was the leading cause of preventable death at this hospital, and it was really the highest type of pediatric mortality where we could make an impact. There are some conditions in children that you can’t change. But this group jumped off the page as an opportunity for change.

After reviewing potential explanations, Shah and Giles concluded that the mortality rate was a result of insufficient sepsis recognition.

Detecting Sepsis

Several barriers exist on the road to detection.

One pediatric challenge is age. A 1-year-old and an 18-year-old have different heart and respiratory rates; care providers with varying levels of experience may miss signs that suggest escalating sepsis in one age group versus another.

“For adults, a healthy heart rate and respiratory rate are about the same across all ages,” says Shah. “But a brand new nurse or resident may not pick up subtle signs that this child has a heart rate that’s too high.”

The time frame of sepsis progression is erratic with no set pattern. Where one patient proceeds to severe sepsis in a matter of hours, another may present later based on immune defenses. Severe sepsis also has no set biomarkers or lab values that define it.

Finally, patients face an array of unique challenges that complicate detection. Young children are unable to communicate exact symptoms, slowing down the diagnosis. Some patients are admitted with comorbidities, which can alter immune defenses and render them more vulnerable. Other patients live with complex developmental disabilities or depend on organ system support. These conditions can shift vital signs, making sepsis even harder to pin down.

“Their temperatures may not be normal, or their respirations are more like a child of another age, or their technological dependence skews their vital signs,” says Giles. “Kids with disease or developmental disability may not display the typical vital signs you see in a healthy child.”

To create a reliable pediatric tool, Shah and Giles had to account for these scenarios. They began by sifting through data from Le Bonheur gold standard cases of severe sepsis, retroactively pinpointing symptoms.

“What we had was information,” Shah said. “Heart rate, blood pressure, oxygen numbers and lab results. We put those together and ran an iterative model to create a rough tool.”

Giles and her decision support team, alongside Amy Guynn Bagwell in Information Services and her IS team, began coding their tool to fit within the framework of Cerner, Le Bonheur’s EMR software. They also incorporated age-specific thresholds for abnormal heart rate and respiratory rate, as well as a linear temperature correction for each age category. In 2014, after a pilot trial and repeated PDSA (Perform, Do, Study, Act) cycles, the tool was ready for use.

Going Live

The tool went live in age-based batches, first used in 2014 for patients aged 13 to 18 years. From 2014 to 2015, 2,646 adolescents were screened.

In its first year, the algorithm’s positive predictive value (PPV) was 53.9%. In 2016, the algorithm rolled out to patients aged 6-12. The algorithm’s PPV jumped to 71.5%. As the team gained insight, they created filters to stop alerts from over-firing: for example, accounting for “sepsis mimics” such as epilepsy, post-operation periods, new trauma and asthma. The algorithm was suppressed on patients with these conditions until 48 hours after admission, reducing false positive alerts.

In February 2019, the algorithm went live for patients ages 1-5. Now, it runs on all Le Bonheur patients ages 1-18.

“Our mortality is down, our response time is better, antibiotics are being delivered in a timely fashion and in general, it has helped overall ICU mortality,” says Shah. The algorithm has aided clinicians in administering antibiotics during the golden hour,”: the first in a three-hour window within which antibiotics best combat infection. In 2018, 135 patients had antibiotics administered an average of 1.2 hours after a true positive alert.

As of 2018, pediatric sepsis had dropped to Le Bonheur’s fifth leading cause of death. Excluding the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), pediatric septic mortality has fallen from 7.6% in 2014 to 4.9% in 2018, below the national pediatric average of 8.4%. Shah is quick to explain that the algorithm is not the only reason for that improvement.

“The tool is also helping raise the level of awareness,” he says. “Opening a clinician’s mind’s eye to the possibility of severe sepsis.”

The Future of Sepsis Prevention

Le Bonheur’s critical care and bioinformatics teams are utilizing the algorithm in a new project, not simply catching sepsis, but predicting it via physiomarkers. The teams analyzed physiologic data that was constantly gathered from PICU patients two to 24 hours before the algorithm fired a true positive alert.

The teams then used artificial intelligence to investigate the data for physiomarkers that reliably predicted sepsis. Several potential physiomarkers were discovered, such as the standard deviation (SD) of heart rate and the SD of systolic and diastolic blood pressure. These physiomarkers could forecast sepsis in advance of the current clinical signals.

In the future, the teams hope to develop technology both sensitive to physiomarkers and integrated with bedside monitors. Where the algorithm relies on intermittent, manual data entry for information, a monitor-integrated tool could continuously update and scan for second-to-second variations in vital signs.

Help us provide the best care for kids.

Le Bonheur Children's Hospital depends on the generosity of friends like you to help us serve 250,000 children each year, regardless of their family’s ability to pay. Every gift helps us improve the lives of children.

Donate Now